Power Query M Version Control using GitHub

See a transparent history of changes to Power Query M functions by using GitHub.

Power Query M Version Control using GitHub

There is currently no obvious version control process to see a history of changes made to Power Query M functions within Excel or Power BI. The Advanced Editor in the Power Query Editor has no built-in function to capture changes made to the query. In other words, it’s very difficult to roll back queries to earlier versions once they’re executed.

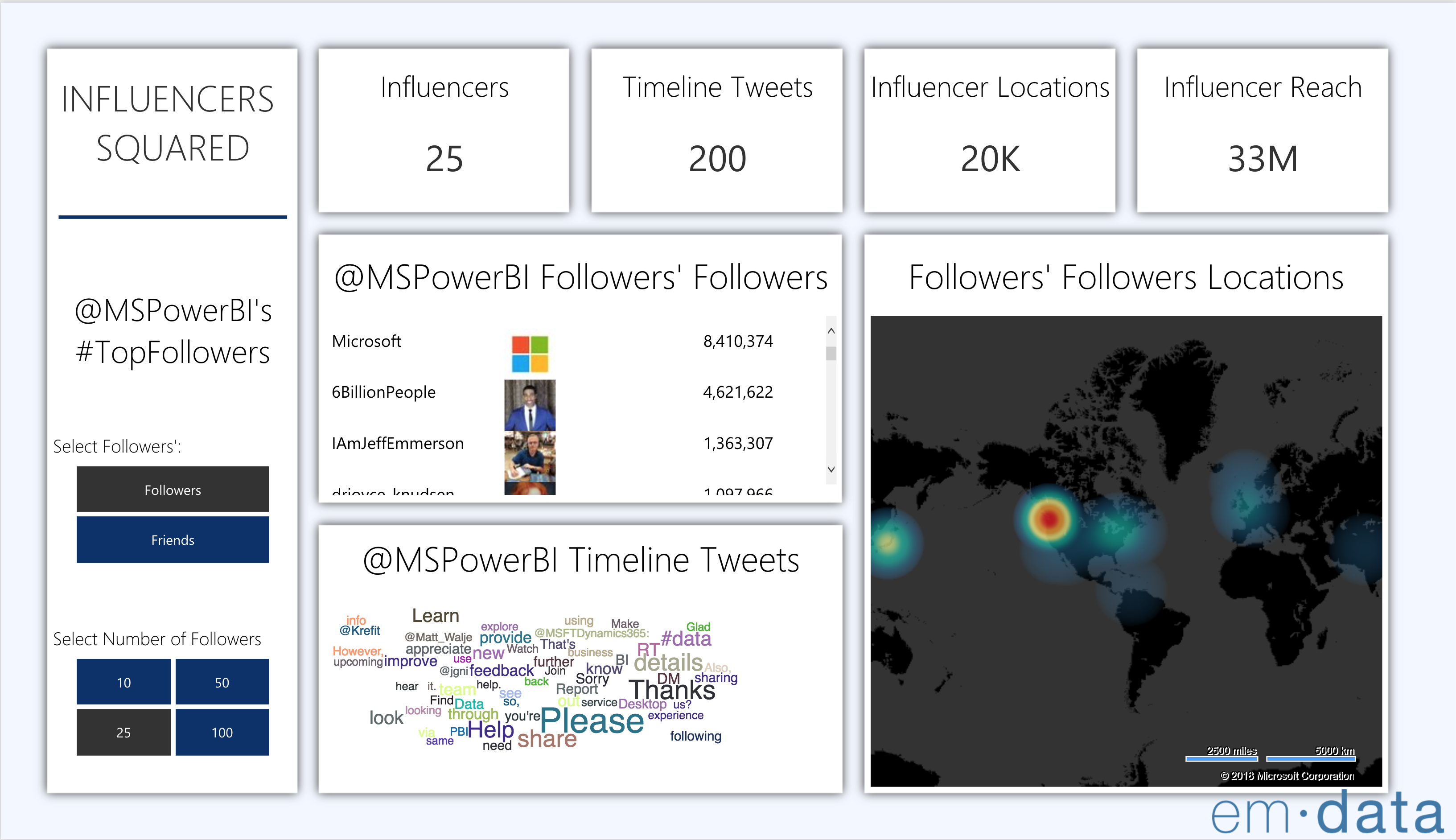

I tend to have a fairly involved data preparation process that I build in to my Power Query M functions. It’s not uncommon for my queries to contain hundreds of lines. Once they become this large, managing changes to my queries starts to become onerous. It’s at this point I often switch from writing Power Query M functions in the Advanced Editor to writing them in a text editor like Notepad++. One of the benefits of separating the functions from the Power BI or Excel file is that I can store the functions in a .pq file on GitHub and see the entire timeline of changes made to the file. Storing .pq files on GitHub becomes especially useful in collaborative envrionments where team members work on the same set of Power Query M functions. And even if you’re working by yourself, GitHub is still useful for those projects that contain a number of queries, like this library of M functions that prepare data from the Socrata Open Data API, for example.

So if I’m not writing these functions in the Advanced Editor, how does the Power Query Editor know they exist? How do we execute Power Query M functions that reside somewhere else?

Expression.Evaluate() and the #shared Environment

Consider the Power Query M code below:

let

Source =

Expression.Evaluate(

Text.FromBinary(

Web.Contents(

"https://raw.githubusercontent.com/tonmcg/powersocrata/master/M/Socrata.ReadData.pq"

)

),

#shared

)

in

Source

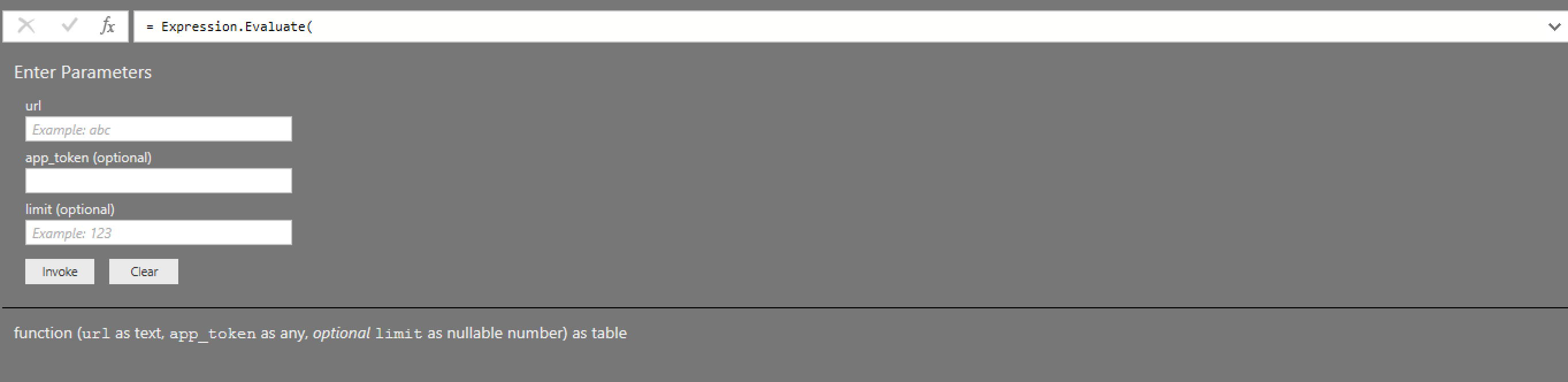

If we copy the code into the Advanced Editor, we should see the following function appear:

The screenshot shows the Power Query Editor rendering a function with multiple parameters. Not anywhere in the code above have we defined parameters. So where did they come from? The answer is I created a custom Power Query M function called Socrata.ReadData() and stored it in a repository on GitHub. I’m using the Web.Contents() function to return the contents of the file and then the Text.FromBinary() function to render the text contained within. The parameters are defined within the function itself, which again, is stored on GitHub.

The most interesting part of the function is the use of Expression.Evaluate(). At its simplest, it evaluates text and returns an evaluated value. In our case, the evaluated text is the text within the Socrata.ReadData() function. The evaluated value is the actual function itself. Put another way, Expression.Evaluate() allows us to make a call to GitHub and return the function’s contents, render the text of the function, and tell the Power Query engine to treat the rendered text as an M function.

But that’s only half of the answer. While the first parameter of the Expression.Evaluate() function requires an expression as text, the second parameter asks for the environment in which the text resides. In our example, I’ve defined the envrionment as the #shared variable. This pattern is what allows a Power Query M function that resides on GitHub to be executed in our Power Query Editor.

I’ll not go into it here, but if you’re interested in understanding the environment parameter and the #shared variable, here is a list of resources that should get you started:

- Lars Schreiber and Imke Feldmann have done incredible work simplifying these concepts

- Chris Webb provides simple examples that help motivate understanding in this area

- Finally, Imke Feldmann uses this pattern often and provides numerous examples on her blog. Here’s one example.

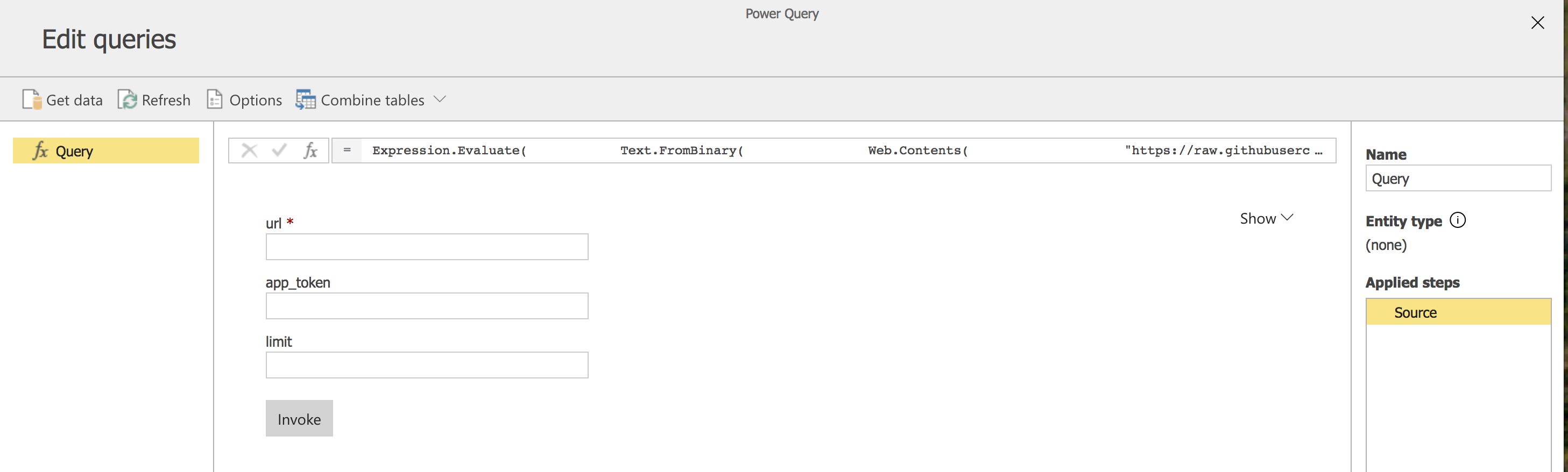

Making it Work in Power BI Dataflows

The most exciting part, however, is that this pattern works not only in Excel and PowerBI[1], but through the browser as well with Power BI Dataflows. We can get the Socrata.ReadData() function to work in dataflows by using the Power Query M code above in the Power BI dataflows Query Editor:

If you want to see what this looks like in action, I tweeted a GIF of this working in Power BI dataflows.

There are boundless opportunities here to use GitHub’s version control system to manage the entire timeline of changes made to projects that use Power Query M functions. Distributed teams around the world can simultaneously work on the code, understand what changes have been made, and collaborate at any time while maintaining source code integrity.

Do you use this pattern as well? What else have you found? Let me know in the comments section below.

Update 13 November 2018

Matt Masson offers a comment in response to this blog post:

Well the gateway infrastructure doesn't support dynamic data sources, and I'm not sure if / when that will happen. I'm also not sure it is wise to ever pull dynamic code from web locations.

— Matt Masson (@mattmasson) November 12, 2018

I think Matt is suggesting this pattern of storing M code on a separate server could open up your application or dataflow to an exploit. If so, he’s absolutely correct. The code above is stored on a public GitHub repository, which means anyone can submit a pull request and sereptitiously inject code that can cause a security vulnerability.

This solution is far from ideal. But the question remains: is there a secure version control system that allows me to see changes to my M code over time? If you have ideas, feel free to leave them in the comments below.

- Be aware: the use of the

#sharedvariable within theExpression.Evaluate()function is not currently a supported feature, which means it can go away at any time.

Twitter

Google+

Facebook

Reddit

LinkedIn

StumbleUpon

Pinterest

Email